After 25 years of teaching at a number of schools in Melbourne, Margaret Hepworth began to question her contributions to society. While the school system was teaching sharing and kindness, across the world: war, violence and greed were still thriving. Three days after attending an indigenous studies conference, she quit her teaching job of 25 years to embark on a spiritual and educational journey.

At this stage of her journey, Margaret felt that she needed to apply her educational teaching to the wider international community. Reflecting on that time, she recalls, ‘I was teaching; I was the head of campus at Preshil at the time. I went to an indigenous studies conference for teachers, which was run by Wesley College (a private, co-educational school in Melbourne). By the third day of that conference, it felt like everyone in the room had moved to a different state of being. For me, it was the recognition that I needed to be working in the area of social justice.’ Margaret had worked overseas before, including three years at an international school in Nanjing, China. The experience had opened her eyes to the value of cultural immersion for clarifying one’s beliefs, values and priorities in life.

‘[So] I walked out of that conference and knew that I needed to resign [from Preshil],’ she reflects. ‘I knew then and there that I needed to go on a new journey in my life. It’s from there that The Gandhi Experiment was eventually birthed.’ Following the conference, Margaret began to question her purpose as a teacher and educator. Furthermore, she started to question the effectiveness of the current schooling system. ‘I needed to step out of the business of teaching, the frenetic nature of teaching and ask myself a series of really deep questions. They were on the lines of, here you are with 25 years of teaching under your belt: what is it, right here and now, that you can give back to the world? Where are the gaps in education? How is it that we say we are teaching sharing and kindness and love, but when you look out in the big wide world, why aren't we seeing all those things? Why aren't we seeing those things in business, in the big corporations, the banking industry? Where does it all go?’

This self-analysis became the trigger that would send Margaret on an educational journey to India. But her journey did not begin without another confronting spiritual experience. ‘It's a bit freaky,’ she recalls. ‘I had begun stepping out of education when I wrote my novel “Clarity In Time”, which came out in 2012.’ The novel, subtitled, ‘A Philosophical and Psychological Journey,’ explored the meaning of life as a series of choices. ‘One morning, I woke up and I was in that state between sleeping and waking,’ she recalls. ‘I literally heard a voice, and this voice said - whatever it means, I don't know - it said, “Go to India, where it all began.” ‘I remember sitting up in my bed …I thought to myself, where what began? What are we talking about here? Are we talking about Buddhism, are we talking about Gandhi?’ Not long after this experience, Margaret met Initiatives of Change (IofC), a global group attempting to build trust and to inspire change at home and abroad. After meeting a young couple at a Muslim Community dinner through Benevolence, Margaret was told about the home of IoFC: Armagh, a 1913 mansion located in Toorak, Melbourne. ‘It was at the first dinner [with Benevolence] that I met two young people who told me that they were living 'in community' at a place called Armagh, the centre for a group called Initiatives of Change. I was intrigued. It was from there that I contacted IofC and was invited to visit Armagh, where I met Barbara Lawler, who was at that time the National Coordinator for IofC. It was Barbara who told me I should go to their conference in India,’ Margaret says.

Margaret didn’t hesitate. She flew to India to attend the Initiatives of Change ‘Making Democracy Real’ conference in Panchgani, India, in January 2015. It was at this delicate stage of her journey that she began to understand the greater idea of non-violence and peace, and how it could be taught. ‘So many things inspired me at that conference,’ she notes. ‘I met people from all over the world. There were two men there in particular, from Lebanon. Both of them had been in the militia, one Christian, one Muslim; they were at war against each other. Now those two men were travelling the world together, talking about peace. It was extraordinary.’

Stories like these inspired Margaret to pursue teaching young people about peace and the non-violent way of living. Spurred on by a new perspective on the possibilities of peace, she began delivering peace education workshops for secondary schools, under the title ‘Global Participation: It Starts With Us.’ ‘We look at all the big global issues out there,’ Margaret explains. ‘Young people love engaging with the big questions about the world. You always get the one about climate change. They can see the link between themselves and their behaviours with regard to the environment. The workshops are about their behaviour, and how they treat other people and the way they reflect to the world. They also learn how you can turn your own anger into a positive thing. By the end of the day, they will be standing up and sharing their own thoughts and dreams…Part of these workshops is about breaking down barriers and building trust.’

The Gandhi Experiment workshops have taken place in schools across Melbourne, involving a range of young people, from students who were once refugees, to those attending elite private schools. As well, Margaret has taken the workshops to schools in Pakistan and India, with the support of IofC’s global network.

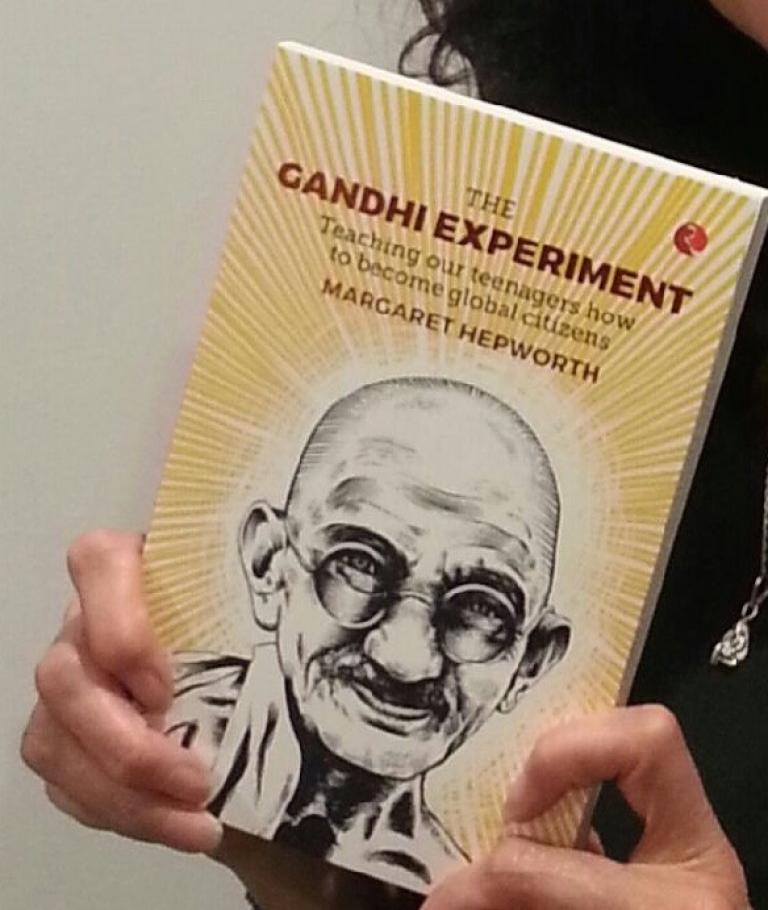

Drawing on these experiences, Margaret has written two works of non-fiction. The Gandhi Experiment – Teaching our teenagers how to become global citizens offers approaches to help parents and teachers instil ethical and global perspectives. Collaborative Debating is a manual for teachers seeking to incorporate peace education in their own teaching approaches. The book encourages a different approach to the traditional ‘class debate’ format, based on having affirmative and co-operative teams of debaters. The goal is to work together to reach a conclusion through a more respectful and understanding approach to discussion and debating. Margaret believes this aspect is key. ‘The book introduces the concept of parallel thinking, from the work of Edward de Bono,’ she explains. ‘It's the idea that we can all come to the same table, and we all have the same goal in mind. So, for example, the goal is to make the world a better place. Whatever it is that we're doing, we work in parallel, we're not going to argue with each other. ‘So collaborative debating removes the adversarial nature of the debate; there's no ranking, no scoring, no judging. There is no one winning over someone else. The win is the solution to the problem. ‘It becomes a far more useful tool for the real world, rather than just arguing for the sake of arguing.’

Margaret hopes that her books and workshops will leave a lasting imprint on young people, and that the idea of collaborative debating and peace education will become an integral part of the education system, not only in Australia, but across the globe. - By Patrick Minkowski

-

The book The Gandhi Experiment – Teaching our teenagers how to become global citizens, will be released in early 2017. The Collaborative Debating manual is available in PDF and will also come out in print in 2017. For more information, or to book a workshop, visit The Gandhi Experiment website.