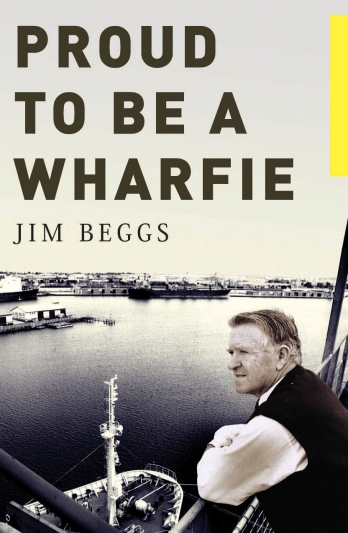

Jim Beggs

King of the wharfies

From No Long Down Under by Mike Brown

There was clearly only one reason why he did it. Jim Beggs wanted to work on the Melbourne waterfront simply because of 'the money'. He had heard that a wharfie (docker, longshoreman or whatever-else you call them) gets 'the wages of the Prime Minister and half the cargo'.

Australia's Prime Minister when Beggs started on the waterfront – conservative Bob Menzies (later Sir Robert, Knight of the Empire, Order of the Garter) – was clearly less enamoured by the waterside industry. At his height of power in the Fifties he claimed that another recession would never get past the shores of Australia because the wharfies were too lazy to unload it. The country was blighted with two pests, he said: wharfies and rabbits.

Between 1951 when Beggs applied for the job as a green 21 year-old and his retirement 41 years later, the number of wharfies working the docks had dropped as dramatically as the rabbit population: from 27,500 to 5,000. It has continued to drop even further. Today a handful of men turn a container ship around in 30 hours, work which 100 men took two weeks to complete in the old days. All you needed then, quips Beggs, 'was a hook, a strong arm and a pack of cards'. It was physical work and the men were tough. A vicious strike in 1928 had left a heritage of hatred, dividing the union; barbed wire separated some of the working areas. Conflicts at times were so bitter that some men finished up, quite literally, 'on the bottom of the harbour'.

'The only time you read about the wharfies was when they were on strike or pilfering something,' remembers Beggs. In one year their union paid so many fines for illegal strikes that a wharfie in the industrial court once yelled to the judge: 'Could we get a discount, Your Honour; we come here so often?'

Young Beggs had a 'flame', a girl he had just become engaged to. He had first set eyes on Tui when they were both 12 years old, at Fairfield State School – and had flicked a folded bit of paper across the classroom onto her desk, asking her to the pictures on Saturday afternoon. She refused, knowing her father wouldn't even consider it. Six years later, after a church-hall dance, they began dating. They were engaged by the time Jim was talking of going onto the docks. But Tui was not very keen on the job. She came from a business family and did not want to be married to a wharfie. They had put down a deposit on a block of land with a one-room cabin in North Balwyn, a developing Melbourne suburb dubbed 'mortgage hill' by its residents. Here they would create the home of their dreams. Tui had a job as a stenographer, 'the thing for a girl to do in those days.' Jim had been working since he was 15 in the shop-fitting business. But they knew they needed more money if they were to build a house. Just for a couple of years, they told themselves, Jim would earn what he could on the docks.

At that stage the waterfront still ran on a system of casual labor. 'When you got to work in the morning there would be about 2,500 wharfies milling around waiting for a job,' remembers Jim. 'Sometimes you would wait for hours and get just 12 shillings and sixpence attendance money.' Beggs was attracted to shift work because it gave him time to start building his house during daylight hours. His initiation was three midnight shifts, unloading about 5,000 tons of potatoes. And during those three nights he earned more than twice the weekly pay of his previous job.

When Tui turned 21 she and Jim married, and moved into their tiny one-roomed 'bungalow'. It was a struggle. The insecurity of casual work and uncertain pay 'has a terrible effect on you,' says Tui. 'We saved for timber, we saved for bricks, we saved to do the wiring.' The waterfront job did not seem to be all it was cracked up to be. 'You were lucky to get two or three days' work a week at that time,' says Jim. 'It was day-work today, midnight shift tomorrow, twilight shift the next. It put a lot of strain on us as a young couple.'

Jim was hammering panel-boards on his new wood-frame house one evening when a helpful outside light was switched on next door. A new neighbour had just moved in. It happened several times, each time giving light for Jim to work a bit later. Then one Saturday a bald head appeared above the fence and its owner introduced himself as Tom Uren. 'The wife's called "Flo" – she never stops talking!' Cackling laughter. Jim thanked him for leaving the light on and cautiously introduced himself. He dreaded being asked what his work was. 'When people found out I was a wharfie, they'd either think I was a Communist or they'd want to lock up the family silver,' remembers Jim. Inevitably neighbour Tom asked the question.

Putting on a brave face Jim replied: 'I'm one of those blokes you read about – I'm a wharfie.'

'Oh, that's where I work too,' replied Tom, cheerfully. Jim was suspicious: he knew the house next door was worth a good bit and had been featured in Home Beautiful. Then it came out that Tom was an accountant, the financial adviser to a stevedoring company which was one of the toughest employers on the docks. What luck, thought Beggs, to move next door to a boss!

But Uren chatted on, saying that the problem was 'fellows in management like me who have made profit our main aim and have created bitterness in the workers'. That caught Beggs' interest. But not as much as when Uren told him how he had given up his top-paid job with a well-known transport company because he disagreed on principle with his managing director's treatment of his employees.

Sensing Jim's embarrassment about being a wharfie, Tom asked outright: 'Do you want to see the waterfront different?'

'Of course,' replied Jim. They had just been through a punishing three-week strike and Jim reckoned it would take 18 months to catch up financially. No-one in their right mind was happy with that. Nor with all the fights and bickering which went with it.

'Well, y'know the place it's got to start,' countered Tom. Jim could think of plenty of others who were responsible – the shipowners and the like. But Tom persisted, 'If you want the waterside to be different, it's got to start with yourself.'

Looking back now Jim accepts that 'blaming has never solved any problems.' But back then during that backyard exchange, it was a new thought. 'In my industry if something goes wrong we naturally blame the employer who blames the wharfies. And the government blames both of us.' With little education, Jim felt 'useless' to do anything to change the situation.

Across the fence Tom suddenly asked Jim if he believed in God? Jim's Irish Protestant parents had got him to church every Sunday. It had meant something to him then. His Bible class teacher had warned Jim against going to work on the wharves: 'You'll lose your faith down amongst those scoundrels,' said the teacher. There was no doubt that five years on the waterfront had had their effect. Jim answered tentatively, 'Yes, I think I still believe in God.'

'Well, y'know,' said Tom, 'God has a purpose for every living soul. Give him a chance and he'll show it to you.'

Jim went inside and told Tui of the extraordinary conversation he had just had. Their friendship grew, not only with Tom and Flo but with others the Urens knew through MRA who took the same approach: that ordinary people could be part of changing what was wrong. Tui remembers being invited next door for a Christmas party and carols being sung. 'We were out here away from our families and didn't know anyone in the area,' says Tui. 'We were very shy and had no confidence. But they made you feel you were worth something.'

Living in their cramped 'bungalow' with the uncertainties of shift work and casual pay, with baby Karen and another child on the way, some of the romance of married life together had worn a bit thin. 'While our marriage wasn't heading for the divorce courts, I wasn't very sensitive to Tui,' Jim says ruefully. 'I had this Irish attitude of walking away and sulking, whereas Tui liked to have things out in the open.' Occasionally they fought 'like Kilkenny cats'. But through the Urens' friendship Jim and Tui found the courage to talk about things they were ashamed of and had hidden from each other.

These changes on the home front gave Jim 'a sense of freedom' as he kick-started his noisy motor-bike each day and set off for the docks. He wondered how things could possibly change there. 'I had no intention of becoming a union official. I just wanted to see what I could do in a constructive way with the fellas I worked with.'

The 'fellas' in Jim's gang were a rough hard-working mob but they had a great sense of humour. One was nicknamed 'The Judge' because of his tendency to come to work and sit on a case all day; another was known as 'Glass Arms', too fragile to lift; and then there was 'Hydraulic Jack' who would 'lift' anything given half a chance. Pilfering was an accepted part of the job. Unloading cans of pineapple on a hot day, one of the gang asked Jim if he would keep watch for him while he nipped into the hold for a feed of the forbidden fruit. Jim stood up to him: 'You do what you like. But I'm not into that sort of caper any more.' Much to Jim's embarrassment, the comment was overheard – and the rest of the gang pressured Beggs to say what had happened to him. Beggs tried to explain that he wanted to become more responsible for what happened in the industry. He had run into a group known as MRA and, as a result, he was trying to live his Christianity a bit more seriously. His mates scoffed, 'Beggsie's gone religious.' Only one fellow, a hatchman, yelled some support from the deck above: 'Don't listen to them, Jim. You stick with it.' He later told Jim an alcoholic friend of his had been cured through MRA.

The incident got Beggs thinking more about the pilfering that went on. Tom, the accountant next door, had mentioned that he had lost business because he refused to put in false tax-returns on behalf of clients. According to Tom, facing things honestly was the first step if you were going to find God's purposes for your life. This bothered Jim. He knew he had nicked a good bit of cargo in his time. Going straight now did not seem to be enough. On his conscience was a clock he had pinched out of a car he had unloaded from a ship. Somehow he could not get past the notion that he should return it, as an act of restitution. Finally he fronted up to the manager of the stevedoring company concerned, put the clock on his desk and apologised for pinching it. 'The manager couldn't believe it,' remembers Jim. 'He told me it was the first time a wharfie had returned a stolen item.'

As it happened Jim had been asked to speak at his local church. He and Tui were finding their way back to a faith and Jim decided to tell this respectable Sunday congregation what he had done in making restitution. He had no idea there was a 'journo' in the congregation. Right out of the blue next day, the Melbourne Sun published an item about wharfie Jim Beggs returning a stolen clock. Before he knew it the story had gone all over the Port of Melbourne. From then on Beggs was known as 'Daylight Saving', the bloke who put the clock back.

Not long after it dawned on Jim that thieving had stopped in his gang: 'We decided that pilfering was anti-union.' He and Tui began to get to know individuals in the gang socially, meeting their wives and families. Gang 59 got a reputation for its team spirit.

Beggs was beginning to feel he could affect what happened, though being responsible went against the grain. 'If this country has got a problem, it's apathy,' he says. 'Those first five years on the waterfront I was one of the apathetic majority in the trade unions of this country.' He had quickly become disillusioned at the first union meetings he attended. 'I saw those stop-work meetings being turned into political football matches between the Left and the Right. When I stayed long enough to cast a vote, I would look around to see where the majority voted and my hand crept up with them. Of course, that soon kills the conscience.' Disgusted, he often took off out the side door and, on one occasion, went duck-shooting instead. 'I thought I was one of the good blokes – raising a family, building a home, going to church – but I was good for nothing because I hadn't got involved.'

Now he wanted to. A challenge loomed – would he offer himself as a 'job delegate'? When a ship berthed some 150 men (in those days) would go onto the vessel to start the job. The first thing they did was to nominate or elect a 'delegate' to be their spokesman while that ship was in port. Any complaints or communication with the bosses went through the delegate. Normally only the politically or ideologically motivated union die-hards would accept the job. Jim plucked up his courage and started offering himself. To his surprise his gang supported him.

Looking back years later he says: 'You don't think you are making history, but the decisions you make can affect a lot. Big doors swing on little hinges. I had no idea they were going to affect the waterfront.'

Another decision had unforeseen consequences. With the Urens' help Jim and Tui had begun experimenting together with the idea that you could bring your problems to God to find some direction on how to handle them. It meant getting up extra early before the morning shift to listen for that inner voice, which seemed to bring results when you listened.

Through this mode of thinking, Jim got the gut feeling that he needed to face up and apologise to a leading Catholic on the docks: Les Stuart, a nuggetty ex-flyweight boxer, 'five-foot-three and seven stone in a wet overcoat'. Stuart was unofficial leader of the 'coalies', the blokes who handled coal, and was nicknamed 'The Washing Machine' because of his reputation as an agitator. Beggs respected Stuart's skills as a soap-box orator and a cunning negotiator. But he was intensely prejudiced against Stuart's Catholicism. It went back to his Irish father, an ardent Orangeman and Lodge member who back in Ireland had carried a hand-gun. He raised young Jim on stories of the vile acts he accused the Catholics of committing. Beggs had voted with the Communists on the docks for years not because he agreed with them but because they formed the main opposition to the Catholics.

In what was long referred to as 'Beggsie's God, Queen and Country speech', Beggs apologised to Stuart. He said as Christians they ought to be working together. At Jim's invitation Les came with some of his 'coalies' to meet the Urens and some of their MRA friends. At the end of the evening Les rose to make his contribution. It was the first time, he said, that he had been in company where they talked of God but hadn't felt ostracised as a Catholic. He decided it was about time to go to Confession again. With a touch of humour Stuart – a militant anti-Communist – told how he had been known to knock-out a Communist or two during union fracas, but he'd come to realise they were still Communist when they came round again. Then he announced he would go and talk with Charlie Young, the Communist secretary of the Melbourne branch of the union, man to man. And he would rejoin the Australian Labor Party, which was split at that time with Catholics on the outer.

Jim's team of like-minded friends in the Port grew, coming from different factions. On the other side from Stuart was a Communist Party member, Les O'Shannessey, who had begun worrying that the class war would inevitably bring a nuclear war. He said Jim had shown him 'a new way'. Fed up with the extremist politics which dominated the union, Beggs considered for the first time standing for a union post. He ran as a middle-of-the-road independent; and nearly got elected.

In October 1961 the national General Secretary of the union, Jim Healey, suddenly died after being in control for 27 years. A well-known Communist Party member Healey had given strong leadership and had welded wharfies in 60 ports around the country into one Waterside Workers' Federation (WWF). The media forecast was that only another Communist could replace him. Just before he died Healey had won re-election by 16,500 votes to 4,000. The challenge galvanised something among Beggs and his wharfie friends. Why should it go far Left again? A Labor Party man, Charlie Fitzgibbon, was put up from the rank and file members. Beggs and crew, though they had no funds nor political machine behind them, became the nucleus of Fitzgibbon's support in the Port of Melbourne.

It was 'a miraculous five-week campaign done in an atmosphere I have not seen since,' remembers Beggs. Night after night they met in a little pub off King's Way, planning and reviewing their strategy. They adopted as a motto: 'Not Left, not Right, but straight.' Election campaigns had always been dirty work, using smears and dubious tactics. Funds were collected on pay-day, the various parties trailing the pay-cart as it travelled round the docks, collecting from wharfies who would support their cause. The rivalry was fierce.

One particular day Beggs and his crew were collecting contributions when they flew past the opposition's car, broken down by the side of the road. A cheer went up in Beggs' car. But the driver, an old 'coalie', slammed on the brakes and backed up: 'You three hop out and let three of their blokes in,' he ordered the men in the back of the car. 'If we're going to win this election, we want to do it fair dinkum.' A few weeks later one of the men they had picked up that day was handing out 'how-to-vote' cards for Fitzgibbon at the election booth. Many like him completely swung over.

Fitzgibbon told them he was bound to lose in Sydney but could pick up a good many of the smaller ports. If he could break even in Melbourne, the second largest port, he had an outside chance of winning. In fact he won by 400 votes in Melbourne, almost exactly the margin he won by nationally.

During the 24 years he was General Secretary of the WWF, Charlie Fitzgibbon 'took us from the brink of anarchy back to the centre of the road and changed the waterfront,' according to Beggs. Tony Street, Minister for Labour in a conservative government, said that prior to 1968 waterside workers were responsible for 21 per cent of industrial man-hours lost in Australia; by 1982, they were causing only three per cent of the loss. Permanent secure employment replaced the hated casual system. For the first 17 years after Fitzgibbon introduced the contract system, not an hour was lost striking for wage agreements. Working conditions were transformed, mechanisation and productivity agreements were struck.

'I take it back to that apology to Les Stuart' (the Irish Catholic ex-boxer) 'and to those days when we began to form that inexperienced but committed team of wharfies on the Melbourne waterfront,' says Beggs.

Waterfront reform seems a perennial challenge – or headache, in some people's view. Back when Fitzgibbon was elected as national leader, Beggs knew their commitment had just begun. The following year they put up a ticket of candidates at elections for the Melbourne branch. Les Stuart won as President but was the only one in the team elected. During the politically turbulent years of the Sixties, there were plenty of ups and downs. In 1965 Beggs won the senior Vice-President's post. In 1971 Les Stuart quit because of ill-health. A bitter election campaign followed in which Beggs gained the presidency.

The elected executive of 17 was composed of five different factions. As Jim was setting out for his first day in office, Tui asked him if he was going to be 'the sixth point of view on that executive?' Before Jim got on his motor-bike, they thought out two principles: 'Not to take sides, and to treat the executive as family.' A couple of hostile members of the executive stuck their heads through his office doorway that first morning saying, in effect, 'Well, you got elected, but stick to Federation policy and keep your morals to yourself.' Primed by Tui, Jim kept his Irish temper in check and thanked his union brother for 'giving me some friendly advice'.

Now and then Tui would come into the office and meet the executive and staff. 'After a while we felt ashamed that we had been so critical of some of them.' Before long Jim and Tui found the sense of family extended beyond the executive to all the members of the union. Their own family bore the brunt of answering phones at all hours, often in the middle of meal-times. 'I learned not to react when the phone rang,' says Tui, 'because twice it was women whose husbands had been killed on the docks. It became a commitment to care.'

At the end of his first year, the Union had a Christmas party for the executive and their wives. One of Jim's oldest opponents, a Beijing-line Communist, invited the Beggs over to sit with him and his wife. 'For eight of the nine years I've been on this executive, I hated the job because of the back-stabbing that went on,' he told them. 'But the last 12 months I've never enjoyed my job so much.' At the next election this man was 'on the stump' telling people that if they did not vote for Beggs they were stark raving mad.

Beggs was re-elected with the highest majority up till then and held the post for 21 years uninterrupted. Then in 1985 he became President of the Waterside Workers' Federation for the whole country. 'King of the wharfies,' headlined the Melbourne Herald-Sun.

During his years as Federal president Beggs visited 40 ports outside Australia, from Rio to Rotterdam, Bombay to Beirut. It was an education. When some of his members found an empty pay packet in a ship hold showing that longshoremen in Canada got paid twice as much as Australian wharfies, he pointed out that their brother-wharfies in Papua New Guinea got one-fifth the Australian rates. Through their affiliation with the International Transport Federation, the WWF assisted over one million seamen on international 'flags of convenience' ships in improving their working conditions and pay to the standards set down by the International Labor Organisation.

Within Australia it is no secret that one group traditionally hostile to the wharfies has been the farmers. All too often they have seen their valuable export orders and competitive edge evaporate because of industrial action, labor costs and poor logistical management on the waterfront. When relations were at their worst, Beggs and two colleagues headed north out of Melbourne to meet an association of fruit-growers in the major production area around Shepparton. 'The atmosphere was so thick you could cut it with a knife,' remembers Beggs, the first time they met. 'No-one cracked a smile.' By the end of the day they were working together, identifying and sorting out the problems. One farmer stuck out a fist and said, 'I never thought I'd see the day when I'd shake the hand of a wharfie.' In one year exports from the Shepparton area quadrupled.

Over years that dialogue developed into a working relationship with primary producers in an effort to keep them exporting and using the port facilities. For years Beggs served on a government export advisory body for perishable commodities. He was not afraid to put pressure on his own members as well as management to get produce moving through the port.

But the biggest battles came as the waterfront came face to face with radical restructuring. Many of the industrial problems were a result of the multiplicity of unions – 27 of them. A handful of workers from any one of these unions could bring a whole port to a standstill, and often did. The Labor government of Bob Hawke, with support from the WWF and ACTU (Australian Council of Trade Unions), introduced legislation to bring reform and rationalisation. Over three years and hundreds of meetings, the WWF executive members sat down with management to systematically remove over 600 'work practices', many of them perks given by stevedoring management to buy peace. These practices had made industrial relations a nightmare. 'Getting the wharfies to work' was the cover story of the Business Review Weekly in 1990, featuring the government's initiative to 'straighten out... the rort-ridden waterfront trade system that costs Australia $1 billion a year'. The BRW highlighted enterprise employment deals and joint venture operations which, in the experience of one meat exporter, improved loading times by 20-25 per cent.

Productivity became the hot issue. Beggs and the union leadership accepted the challenge and took flak from their own members. At the same time Beggs held management responsible. In his view many in management lacked the nerve or imagination to confront the issues and to manage change, preferring instead to rely on arbitration or to simply cave in. When one company wanted to close an unprofitable dock, Beggs' team proposed an incentive scheme which abolished some old-established perks and wasteful work-practices. It was tried and productivity rose 300 per cent.

Forty-one years after Beggs first picked up his hook and walked onto a dock, one consolidated Maritime Union of Australia was formed, incorporating 27 unions. Their agenda stressed multi-skilling, training, career-path planning for all workers and wages geared to productivity.

It was the climax of Beggs' leadership on the waterfront, his crowning achievement. But even as the consolidated union Beggs had worked so hard for was coming to birth, his leadership was being ruthlessly undercut by various power groups, manoeuvring for control of the new body. In October 1992, the ground cut beneath him, he retired as the last elected national president of the Waterside Workers' Federation before that name passed quietly into the history books. Accepting a package offered as part of the government's restructuring, Beggs himself joined those leaving the waterfront, earlier than planned. Some of the new national leadership were only too glad to see him go. They played a different game. The Daily Commercial News, referred to as the 'shipping bible', commented that the departure of Beggs and his general-secretary, Archie Arceri, meant the 'waterfront reform process has lost its two best advocates.'

Within months of their leaving, a major national strike by the new Maritime Union – in which the more militant former Seamen's Union members had begun to push their agenda – broke the record of years of strike-free wage negotiations. Their action cost the country millions of dollars, forcing the Keating government to intervene. The docks have been anything but peaceful since.

Beggs, for his part, defends the 'quiet revolution' which transformed conditions and efficiency over the past 30 years. At the same time he is the first to admit that entrenched interests still blight the industry. More structural change will be needed. But when Beggs talks about the waterfront, it is not agreements and statistics that he quotes but people and their attitudes. That is where changes are still most needed – on both sides. 'One of the fears I have for the union movement today is that we have lost our goals,' he told a conference in Melbourne in 1982. 'Some of the founders of the union movement talked of the brotherhood of man under the fatherhood of God. Today some still want shorter working weeks, bigger pay packets, and less responsibility. That's another form of materialism, the very thing we as trade unionists condemned in those who were against us in the early years.'

There is no longer any room, in Beggs view, for using the waterfront industry to further political or ideological interests. 'Unless we learn to find a consensus with those we traditionally put on the other side of the fence, we have lost the battle to build the new society that our union movement was formed for.'

Fundamentally that new society depends less on ideologies and policies than it does on the moral strengths and energy of individuals to bring change, he argues. 'I have to remind myself that it wasn't by accident that I landed into that job. God put me down on the waterfront. When I remember how I was one of that apathetic majority, I know there is always something I can do to bring change, starting with myself.'

Caroline Jones interviewed Beggs for her ABC program, The Search for Meaning. 'Many people today feel rather powerless,' she concluded. 'Your way of life suggests that as an individual I do have some power to make a difference.'

'I'm absolutely convinced of that,' replied Beggs. 'I am an ordinary person, with not much education. But history is made up of individuals who have turned the tide and most of them have been ordinary people. I say to people who ask, God has a plan for your life. You may not be meant to become a leader of your profession. But if you try that experiment my wife and I made 35 years ago, you will have that peace of heart which is more important than wealth and power. And you will never know the effect you have.'

Beggs' story, of course, will have its critics and doubters – those who never had a good word to say for anything on the Australian waterfront. They point to statistics which show handling rates in Asia and elsewhere apparently outstripping those of Australian ports.

During a break from digging his back garden at Balwyn, Jim digs into a file and hands me a letter. 'Here, mate, have a look at this.' It is from Peter Strang of Strang Patrick Stevedoring, dated June 1992, four months before Beggs was given the shove. Attached to it is a chart showing terminal productivity in 22 ports around the world; the Port of Melbourne came third. 'We appreciate the contribution your members have made to producing this result,' wrote Strang.

Six years later the same company, as Patrick Stevedores under the control of Chris Corrigan, took on the closed-shop power of the Maritime Union. With help from the Howard government, Corrigan introduced non-union Dubai-trained labor, protected by balaclava-clad security guards and Rottweilers. The Melbourne waterfront saw the worst pitched industrial battles for decades. When it ended both sides claimed victory. Patrick's boss Corrigan and Industry Minister Peter Reith boasted that it was the biggest breakthrough in 40 years. Half of Patrick's 1400 workforce took redundancies and left the waterfront. On the other side 'unionism hasn't had such a boost for years,' observed The Age, saying wharfies were 'recast as the valiant defenders of worker power.'

Having saved his company some $40 million a year on labor costs and increased its value on the stock exchange, Corrigan, as a principle shareholder, was reckoned to be personally $3.4 million richer. And why not, some might ask? Beggs, at the start, admitted he had gone onto the waterfront for one reason only: the money. But the difference was what happened to him during the years he was there – the 'restructuring' of his core motives which made his leadership effective.

When he returned that clock he had stolen from the cargo, Beggs' mates dubbed him 'Daylight Savings Jim', for 'putting the clock back'. Which often struck me as odd, for Daylight Savings is when you put the clock forward. Perhaps it was prophetic, after all. For Beggs in fact helped move the clock forward, through his 'daylight' honesty and his keen sense of responsibility. And without such values our highly-competitive, deregulated, globalised style of enterprise will leave more and more people steadily sinking to the 'bottom of the harbour'.