Comparing Cambodia’s Lost History of Rock ’n’ Roll with the Protest Era of The Beatles

The Cambodian genocide is a subject we in the West are taught little, if anything, about. Mark Russell ponders on two films that offer contrasting studies in freedom, and asks where Australia’s protest songs of today can be found.

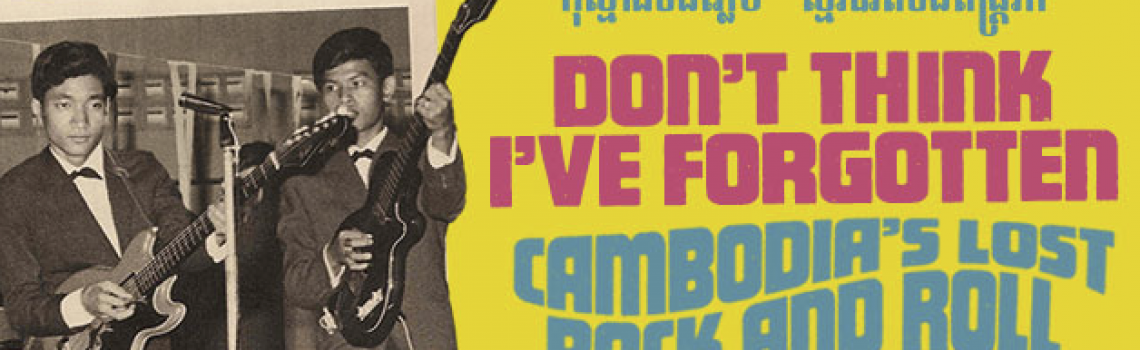

Any link between The Beatles and Pol Pot is tenuous at first glance but, as the 2014 documentary Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten shows, rock ’n’ roll was an effective weather vane for the political climate in ‘60s and ‘70s Cambodia.

Initiatives of Change showcased Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten on Thursday 30 November at Armagh in Melbourne. The documentary is a philosophical corollary to its recent screening of Across the Universe (2007) – a musical built on Beatles songs, which follows two star-crossed lovers as they navigate the turbulence of the free-love era.

Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten offers a deeply affecting portrait of Cambodia’s descent into a dark revolution that would kill an estimated 25 per cent of the population. It’s an engaging, if troubling film. Director John Pirozzi paints the introductory scenes with liberal doses of nostalgic innocence, hinting at looming storm clouds but mostly relying on our own knowledge of the events that would follow. This makes it all the more powerful when, inevitably, these events arrive. We watch as the burgeoning movement towards freedom of expression is crushed beneath the plough-wheel of the Khmer Rouge.

By comparison, the feature film Across the Universe, which screened at Armagh on 2 November, lacks this deft handling of its subject matter. It’s not a terrible film by any means, but director Julie Taymor falls short of the mammoth task she set herself. The plot itself offers touch-points, hammered along the running time to give something to hang the (no doubt extremely expensive) songs from. With a Little Help from My Friends drops in when new friends meet. Hey Jude plays when a character named Jude needs consoling. The movie does wear its themes on its sleeve, however. This makes the link to Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten clearer to see, because while the doco mentions the influence the Beatles had on Cambodian rock ’n’r oll, the real connection is the central message the films share: that art, and specifically music, can fight any evil.

Both Across the Universe and Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten are studies on freedom: Western counter-culture’s belief that the greater good required embracing personal freedom, versus Pol Pot’s certainty that it meant violently squashing it. In both instances, the filmmakers assert that true freedom requires holding onto ideologies and passions in the face of overwhelming horrors, and that killing an idealist does not kill the ideology.

Paying this cost, and the way it changes your perception of freedom, is another common thread between the stories.

In Across the Universe, the main characters Lucy (Evan Rachel Wood) and Jude (Jim Sturgess) are crafted as personifications of the time. Through the early ‘60, they move through the world buoyed by teenage naiveté, reflecting the idealism and boundless potential felt by society at large. The boom in progress around racial, sexual and sexuality attitudes becomes the backdrop of their romance. As the decade storms on and the Vietnam War becomes an ever-growing force, Lucy and Jude’s demeanours sour into disillusionment and militant protesting.

Similarly, Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten begins in a Cambodia that seems utopic in its positivity and thriving arts scene. This was a country where even the Royal Family contributed to the creation of music. We’re introduced to the crooners, sirens and rockers who shaped the national spirit. But as the War gains momentum – not oceans away, but snapping at the borders of Cambodia itself – we sense that this spirit, and some of the artists, won’t make it to the credits.

Still, that core message survives – that music is a force for good in troubled times. That singing a song can be the tiny candle that lights the way through the gathering night of oppression. This gives us a clear lens through which to view our own opinions of music and art as weapons of freedom.

Is the artistic defiance that crafts a chart-topping anti-war anthem the same force behind a woman standing in a field singing a working song, knowing that if the soldiers hear she’ll be killed?

In Australia, in the current climate, we’re a long way from being truly silenced. We have the freedom to perform any song we like – to directly criticise and satirise our government in any way we choose. Yet if it wasn’t for A. B. Original’s recent hit January 26, we might have to go back to the Whitlams and Blow Up the Pokies to find a truly popular Australian protest song.

The wars and injustice haven’t stopped. So have the artists lost their voices, or have we stopped listening? – Mark Russell